Poem published in the California Assembly Journal at the request of Assemblyman Frank D. Lanterman, June 18, 1965.

IT wasn’t wanted.

Especially by those in its path. La Cañada’s 2.5-mile section of the Foothill Freeway held millions of dollars of federal funds for California in the balance. Every step of the way, the people of La Cañada fiercely battled against the freeway, even taking their fight all the way to Washington to keep it at bay.

The Foothill Freeway had been in the minds of both the Federal Government and the State Division of Highways since the 1940s. La Cañada’s 2.5-mile section of the Foothill Freeway held millions of dollars of federal funds for California in the balance. Included in the transit master planning of the Los Angeles County Regional Planning Commission in 1944, the Foothill Freeway was an idea that was continuously advocated for throughout the 1940s and 50s by various transportation and engineering boards, including the Automobile Club of Southern California.

The location of the National System of Interstate Highways was designated in 1955 by the Bureau of Public Roads of the U. S. Department of Commerce. At the time this map was created in 1957 by the California Division of Highways, the only freeway that did not yet have an adopted route was the Foothill Freeway.

The early section of the Foothill Freeway went from the east side of the Arroyo to Foothill at Gould Avenue.

In 1955, a small segment of the Foothill Freeway was constructed near Devil’s Gate Dam. This was done to help alleviate the heavy congestion at the crossing of Devil’s Gate Dam and the Arroyo Seco. At the time, authorities said that the road had been built in “freeway style” simply because that was the most practical way of building it. They also said that it did not “imply any extension of a new route…although a Foothill Freeway in the future is probably inevitable.”

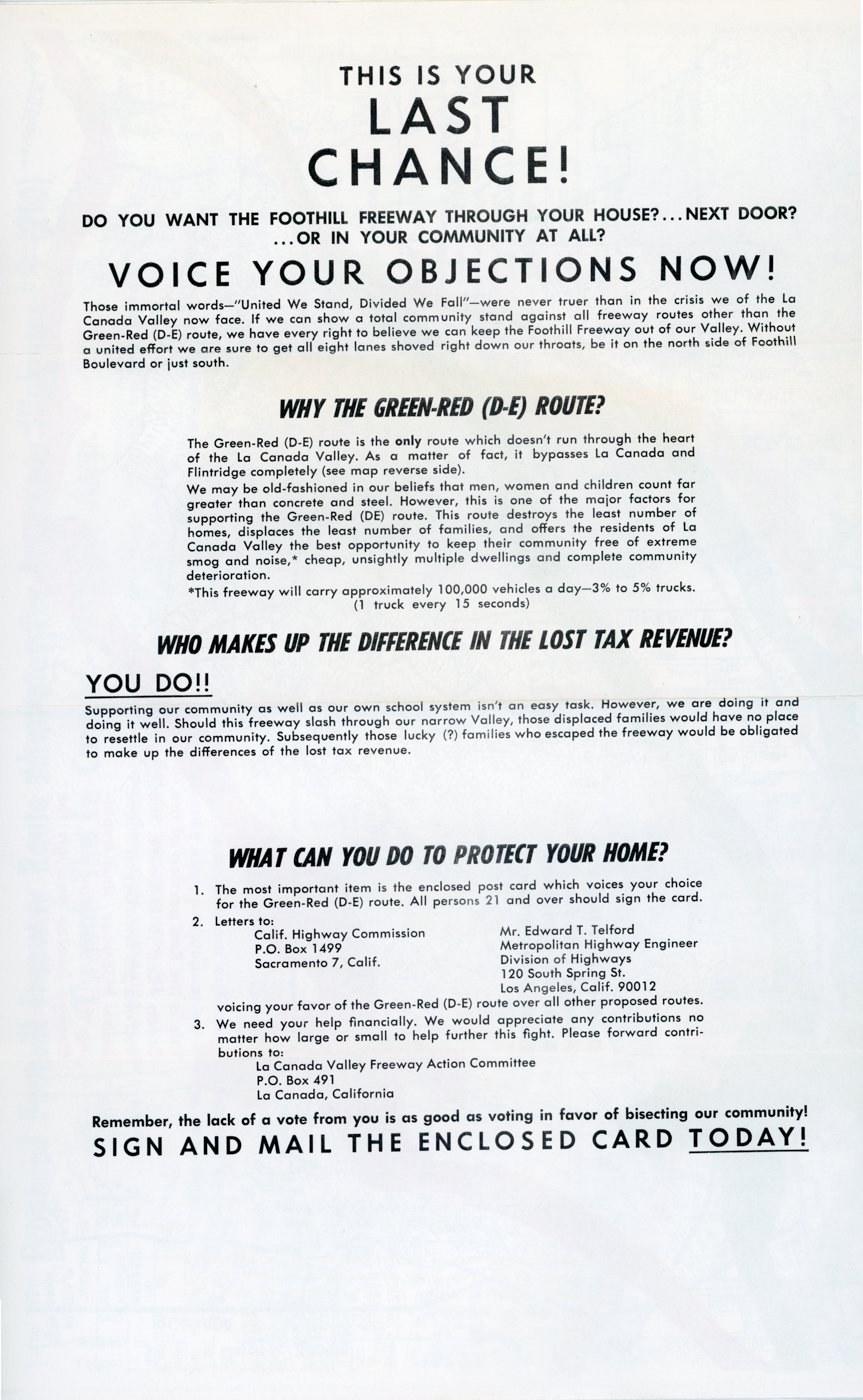

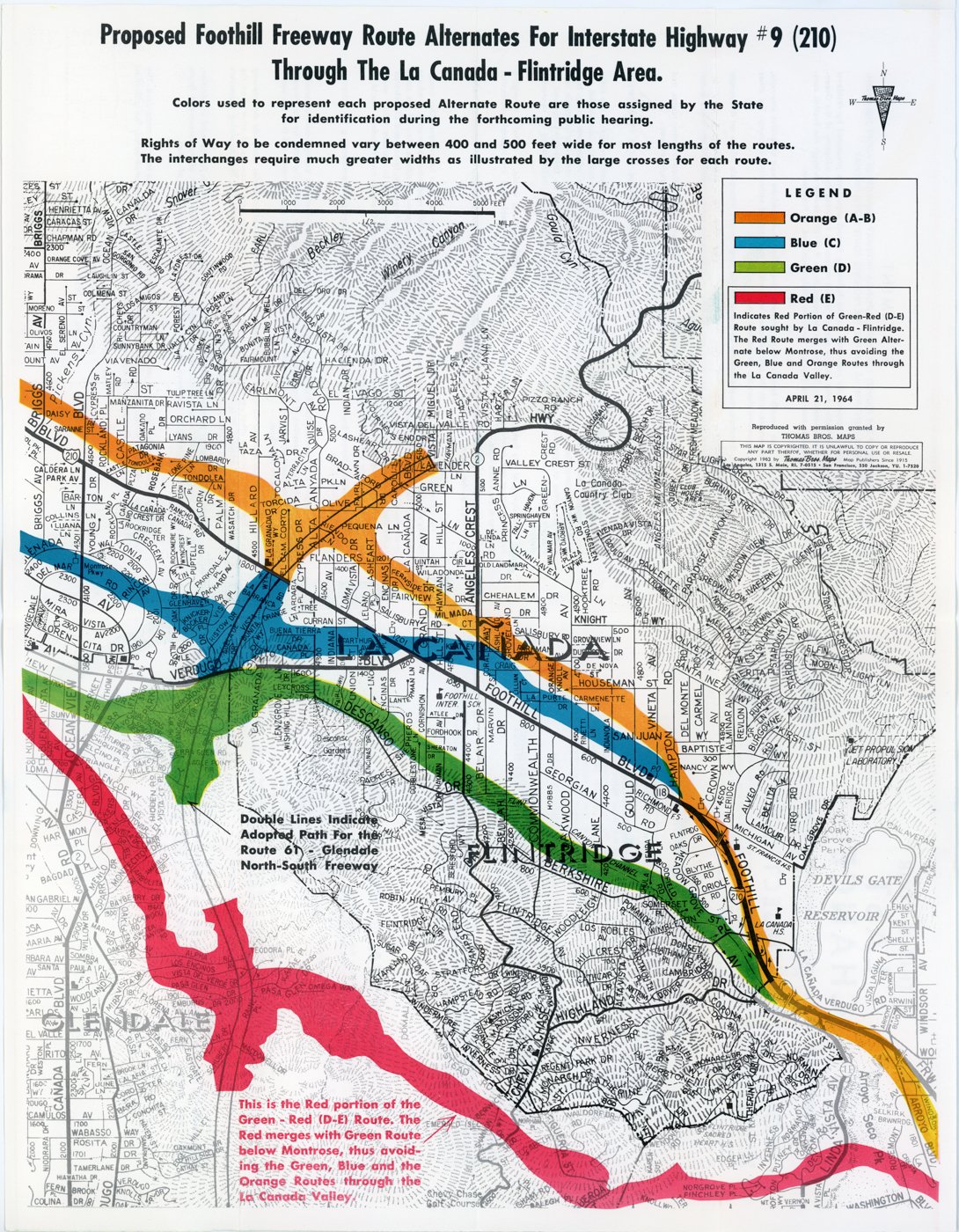

The freeway became more than just talk in April 1963, when the La Cañada Coordinating Council sponsored a meeting on the status of the freeway master plan with the State Division of Highways. More concern was raised later that year when, during a second meeting, the Division of Highways began to introduce the public to its freeway route studies for the area. The different route alternatives all threatened to bisect La Cañada, destroy historic buildings, and one would even wipe out part of Descanso Gardens. It was at this meeting that the La Cañada Valley Freeway Action Committee (LCVFAC) was born.

The 5 routes proposed for the 210 Freeway proposed by the by the State Division of Highways. Map created by the La Cañada Valley Freeway Action Committee (LCVFAC). Published in the La Cañada Valley Sun May 2, 1963.

The LCVFAC was an independent group made up of major organizations concerned about the routing of the Foothill Freeway through the valley. It included the La Cañada Unified School District, local PTAs, Kiwanis Clubs, other school groups, Rotary Club, the Chamber of Commerce, Descanso Gardens, as well as property and homeowners’ associations in both La Cañada and Flintridge. This group would become the main unifying force against the freeway. Their logo, seen at the beginning of this exhibit, is a dragon with a truck for a head and a highway for a tail about to attack the La Cañada Valley. The LCVFAC argued that the freeway would cause an unequal burden of noise, pollution, school district tax loss, and most importantly, be way too large for such a small valley.

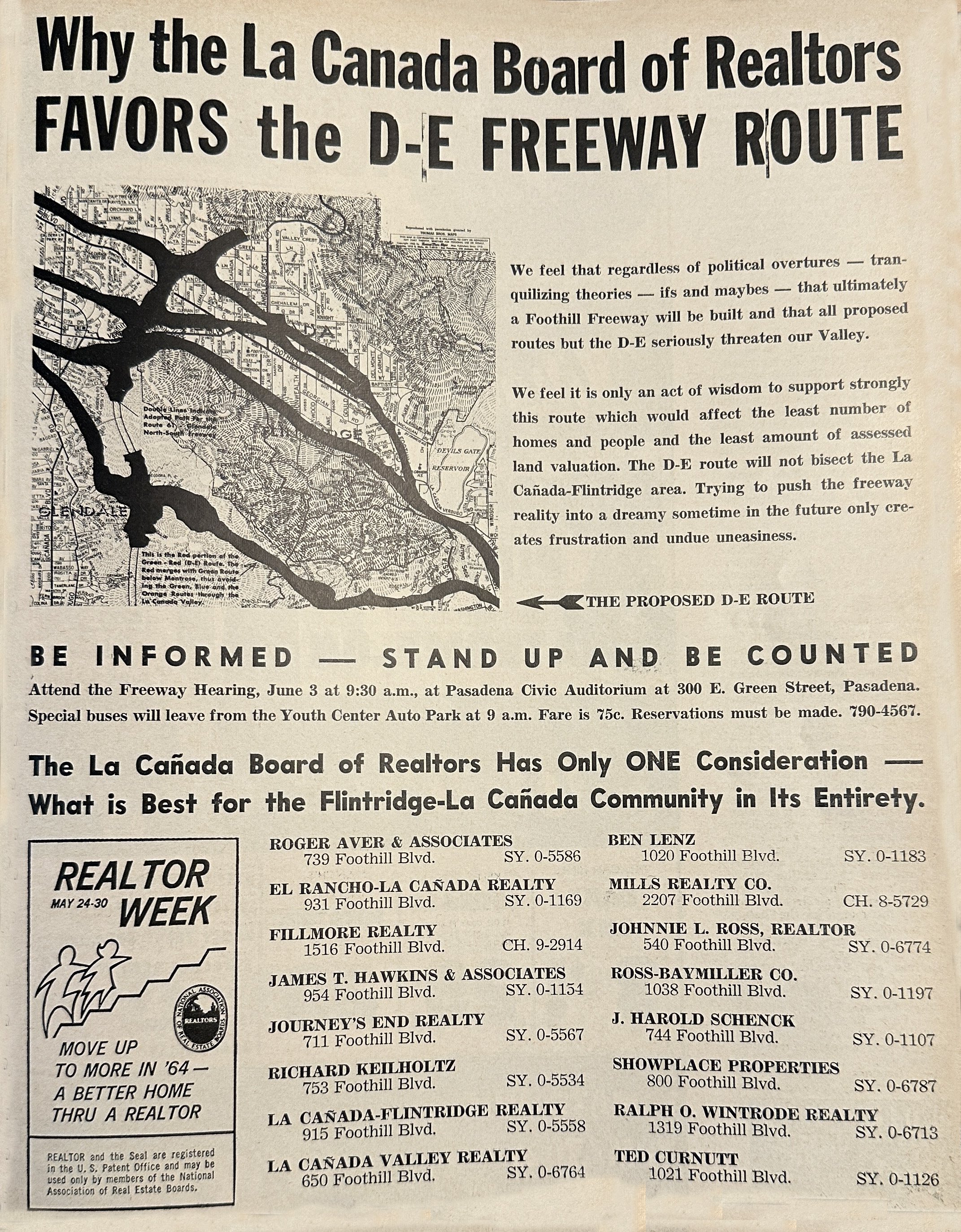

The only route that was remotely acceptable was what was called the “D-E” route, a combined route that would bypass the valley to the south and would affect the fewest number of living units of all the routes. This alternative bypassed the southern border of Flintridge at the Figueroa-Chevy Chase intersection, which would be the closest point the freeway would get to Flintridge. In May 1964, the LCVFAC sent out a survey to residents, receiving over 5,000 signed cards requesting that the State Highway Commission adopt the “D-E” route. This was in addition to the endorsement of the “D-E” route by twenty-three La Cañada and Flintridge organizations.

On June 3, 1964, an important public hearing was held by the State Division of Highways. At the time that La Cañada community groups and city leaders were slated to speak, over 900 La Cañadans came en force. The hearing lasted 13 hours over two days.

The two-day freeway hearing occurred at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium. Image published in the La Cañada Valley Sun, June 6, 1964.

Frank D. Lanterman, CA State Assemblyman, 1951-1978

State Assemblyman and La Cañada native son, Frank Lanterman, made a strong stand, stating that more time was needed to study the routes. He argued that “we are running into grave danger because we are considering only the driver benefits but must also evaluate the long-range effect on the community.” Earlier in May, he had submitted H.R. 307 to the Assembly’s Transportation and Commerce Committee, which would have given the State Highway Commission time for further study of alternative routes, but it had been defeated.

Another major ally at the meeting and throughout the freeway fight was Warren Dorn, Chairman of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors and a La Cañada resident. He urged the Highway Commission to abandon the Foothill Freeway completely and instead designate the 134 Freeway, a state highway, as part of the federal highway system. He felt that most of the impetus for forcing the Foothill Freeway project forward was the need to spend federal funds as quickly as possible.

Warren Dorn, Member of the L.A. County Board of Supervisors, 1956-1972

Leslie C. Tupper, officer of the LCVFAC and Board member of LCUSD.

In July 1964, State Engineer J. C. Womack recommended the Foothill Freeway follow the “C” route, which ran directly through La Cañada, dividing it straight through the center. The decision became even more final on November 18, when the dreaded “C” route was confirmed by the State Highway Commission. Leslie Tupper, at the time a Board member of LCUSD and an official of LCVFAC, went up to Sacramento in December to plead La Cañada’s case. He went before the Highway Commission, requesting that the alternative “D-E” route be reconsidered. The request for appeal was denied and La Cañadans were so devastated that the Valley Sun’s editor even made an appeal to Santa Claus on the town’s behalf to change the Highway Commission’s mind.

Also called the “Blue Route,” the “C Route” favored by Womack was actually a combination of the C, A, and D. Routes. Image published in the La Cañada Valley Sun August 6, 1964.

The State Highway Commission gave the L.A. County Board of Supervisors the street closure agreement in July, 1965, which would allow for construction to begin. As Chairman, Warren Dorn said that he would not sign the agreement if the Commission was going to build the freeway without further study. He used the agreement as leverage by blocking the entire 48-mile 210 project, keeping over $320 million dollars of federal funds for the whole state of California hanging in the balance. All work on the freeway needed to be finished and reimbursed from the federal government by the end of 1972. A study of alternative routes was requested, and the Board of Supervisors again requested that funds for the La Cañada portion of the freeway be transferred to other federal projects.

In the meantime, La Cañadans took their concerns about the Foothill Freeway routing decisions all the way to Washington. Leslie Tupper, representing the LCUSD and the LCVFAC, met with Rex Whitton, an administrator of the Federal Highway Administration. Unfortunately, Whitton sent the L.A. County Board of Supervisors a telegram urging them to approve the street right-of-ways for the freeway. The Board heeded his word, and the right-of-way agreement was finally signed in June 1966. The battle to keep the Foothill Freeway out of La Cañada was over, but the LCVFAC continued to speak for the community, pressing the State Division of Highways for 1) a depressed highway and 2) maximum landscaping along the route through the community, both of which were granted.

The La Cañada Valley Sun stated that “No place is too far to travel when it comes to keeping the freeway out of La Cañada, not even Washington, D.C..” published on May 26, 1966.

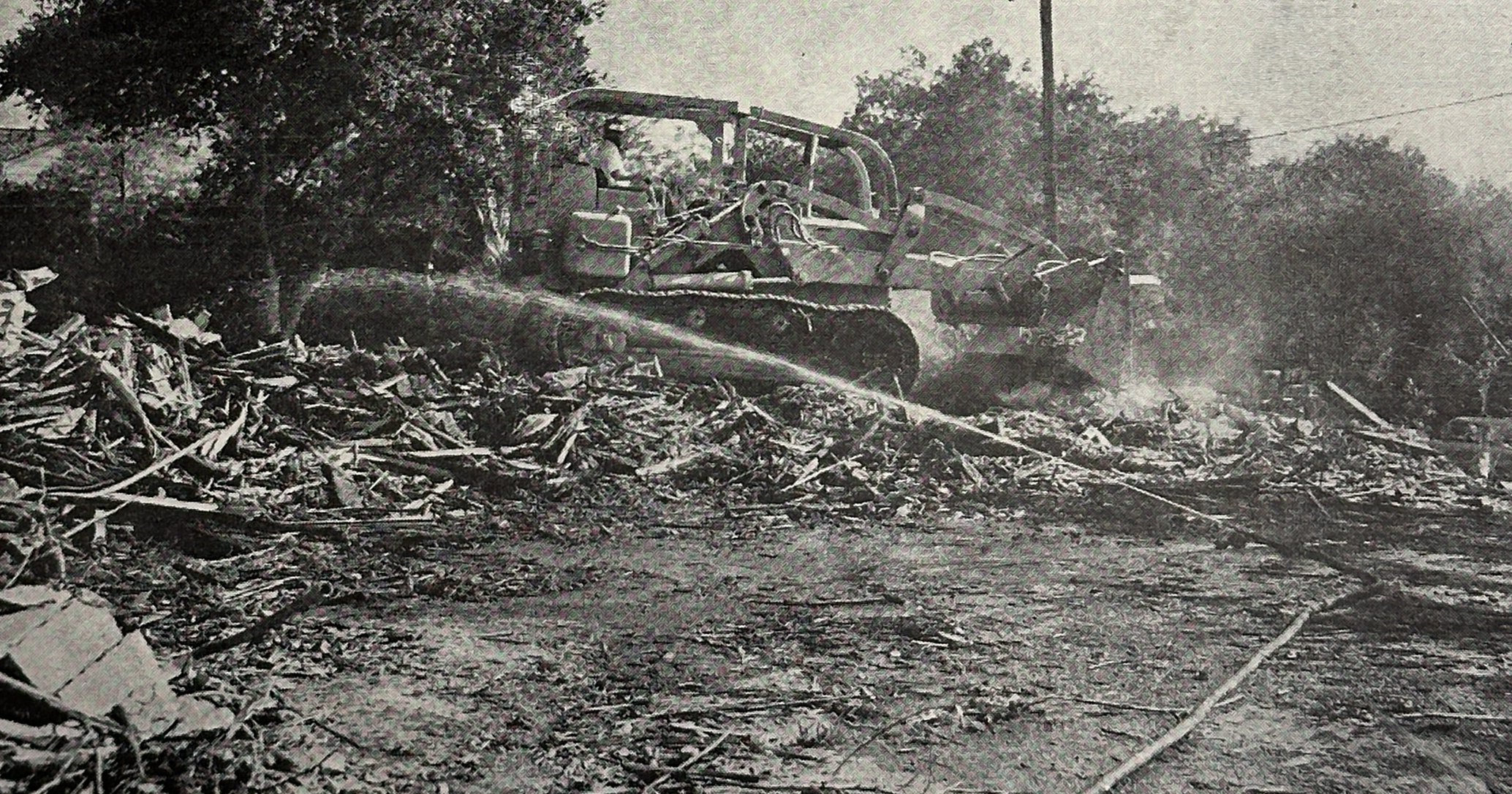

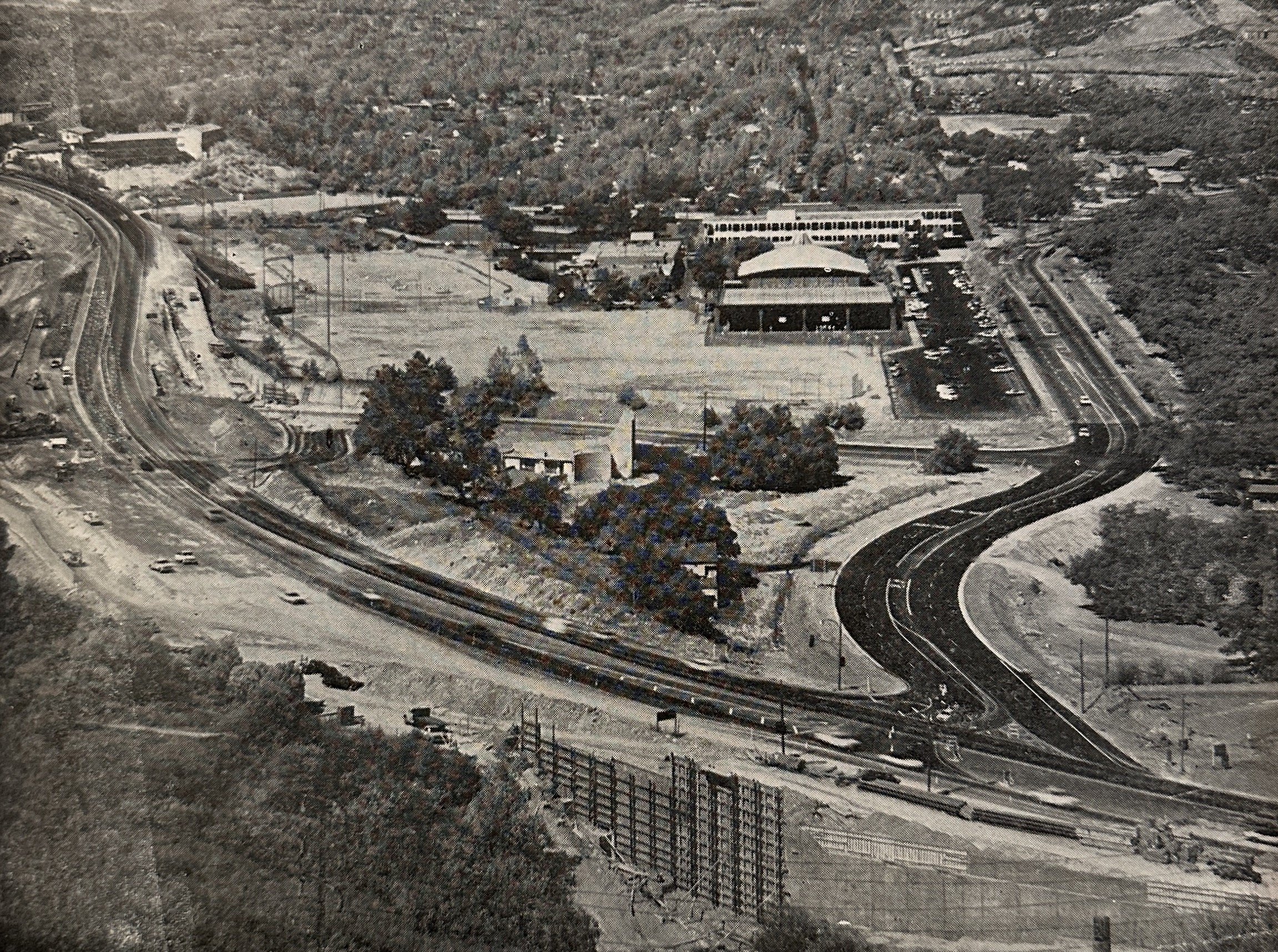

The State began to purchase La Cañada homes in 1967, with a total of 551 purchased by 1969. Land belonging to the La Cañada Unified School District was needed to create the detour for building the freeway tunnel. One of the more prominent victims of this was the old La Cañada Elementary School, which the state purchased for $857,000 to be knocked down. Property belonging to the Church of the Lighted Window was also temporarily “borrowed” by that State for the Foothill detour. The detour, built between Cornishon-Grand Avenue and Lasheart Drive, opened in April 1969.

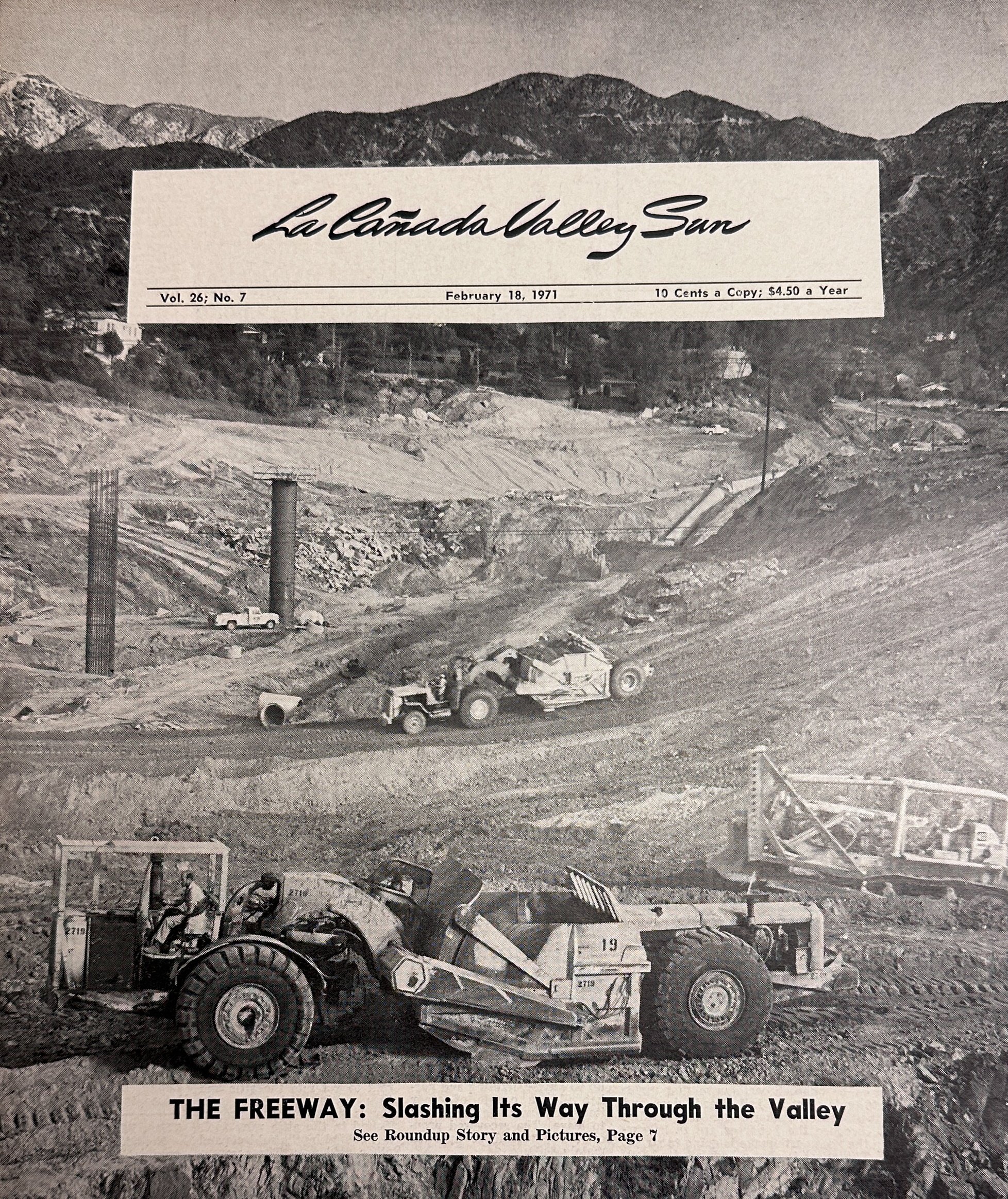

Over 250,000 cubic yards of dirt were moved to make room for the freeway tunnel, which now runs under Memorial Park. Cover image, published by the La Cañada Valley Sun, July 10, 1969.

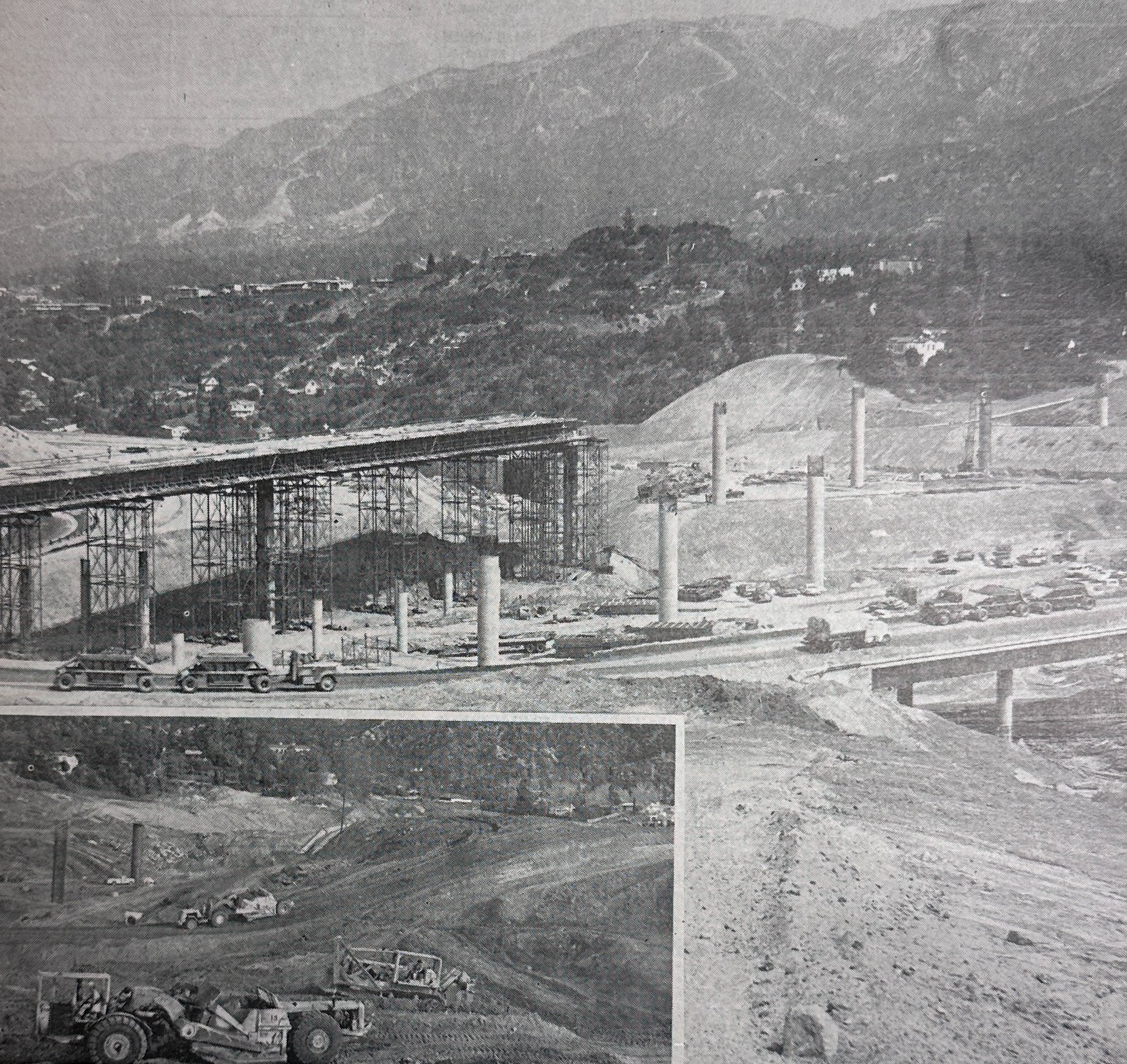

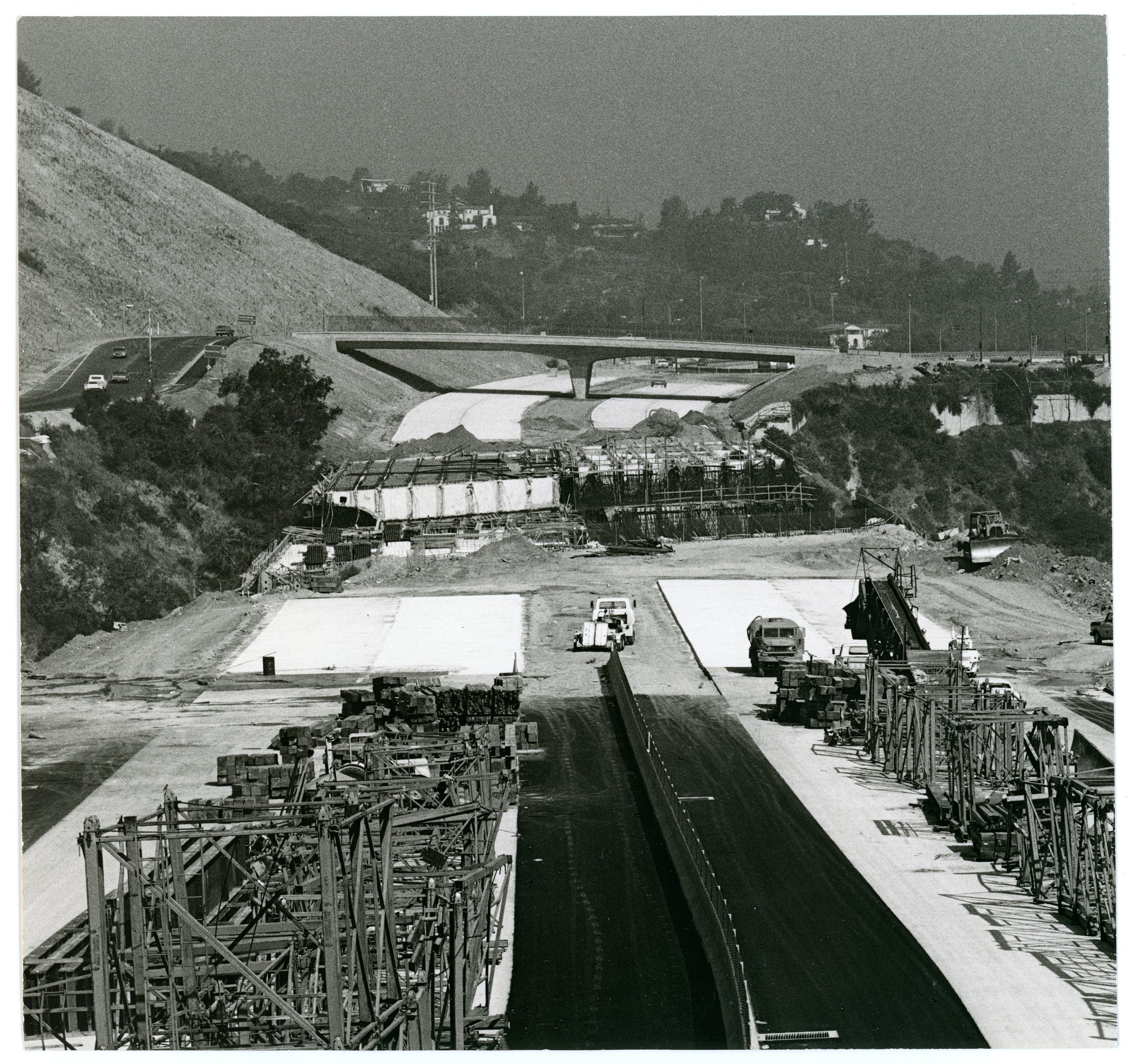

Construction of the tunnel portion of the Foothill Freeway at the intersection of Foothill Boulevard and La Cañada Boulevard began in the summer of 1969. The tunnel runs 620 feet long and consists of 50,000 tons of steel and concrete, as well as over 13,000 miles of ½” diameter steel rebars running through the tunnel. It also features day and nighttime lighting, as well as an antenna system whereby radio calls and radio reception will continue inside it without any interruption.

The construction of the freeway itself began in December, 1970 and involved over 200 workmen. The depressed freeway was built thirty feet below the surface, with five drivable bridges in La Cañada built over the freeway on Gould, Oakwood, Commonwealth, Angeles Crest, and Alta Canyada. The entire La Cañada section of the freeway was built at a cost of $19,214,000, with 90% of the project paid for with federal funds. Beautification of the buffer area and Foothill Boulevard were incorporated into the project, thanks to the efforts of the LCVFAC, including the undergrounding of all the utility poles on Foothill Boulevard.

Prior to the opening of the La Cañada portion of the Foothill Freeway, the Assistance League of Flintridge hosted a community-wide celebration on October 21, 1972 on the freeway itself. No formal written invitations were sent out; rather, people were alerted via word of mouth and the Valley Sun. There were 261 tables set up inside the freeway tunnel—one for each street listed in the current La Cañada directory. Radio’s comedy duo Al Lohman and Roger Barkley were the emcees, and three bands entertained the crowd of over a thousand.

Cover of the October 12, 1972 issue of the La Cañada Valley Sun.

The first car on the 210 Freeway was soon overtaken by a speedy red Porsche that passed it almost immediately!

The Foothill Freeway finally opened on November 30, 1972 to very little fanfare. Westbound lanes were opened at noon, then eastbound lanes were opened three hours later. The first “regular” user of the new freeway was driving a yellow Datsun, who waited for four hours to have that honor. Several others had surreptitiously driven along the new route for many weeks.

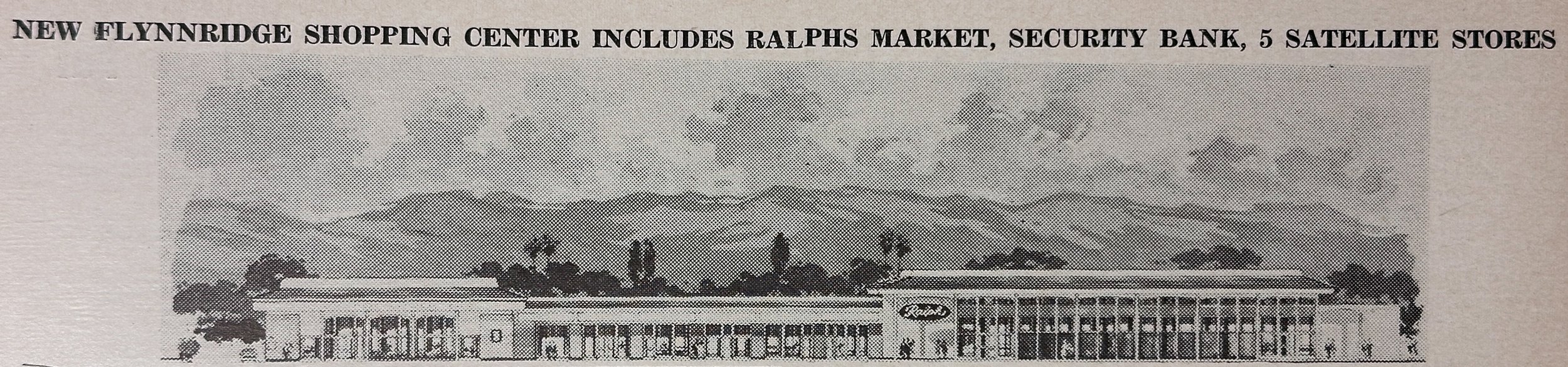

The 210 Freeway caused a lot of heartache and loss for the people of La Cañada. The freeway itself changed the landscape of the valley, and so, too, did rezoning of the areas surrounding it. The La Cañada branch library, post office, and La Cañada Elementary School were all in the freeway’s path and received new locations. New shoppings centers cropped up along Foothill Boulevard where zoning changes in La Cañada’s master plan called for retail construction. Flynnridge Shopping Center, home of Ralphs grocery store, as well as Plaza de La Cañada Shopping Center, the present home of Gelson’s grocery store, are just two retail centers that replaced some of the homes taken down for the freeway.

Photo of the Foothill Freeway soon after its completion, November, 1972, from the La Cañada Valley Sun Photo Morgue in the Lanterman Archives.

La Cañada would never be the same, but it was not divided as a community as many had feared. And although their efforts to be involved in the decision-making of the 210 Freeway’s route failed, the community and the LCVFAC paved the way for legislation to be passed that required local input in all future freeway projects in California.